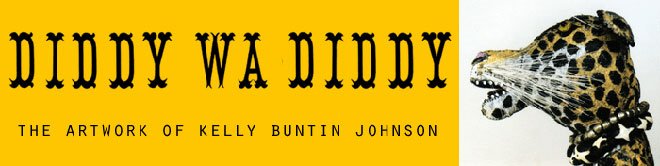

Thylacine

Thylacinus cynocephalus (pouched dog with a wolf head)

EX (extinct)

12"x6"x7"

mixed media sculpture, painted, hand stitched and beaded leather

April 1930

EW (extinct in the wild)

Last confirmed Thylacine in the wild was killed

7 September 1936

EX ( extinct)

Last Thylacine died in Hobart Zoo, Tasmania due to human neglect

A prehistoric survivor, the Thylacine, thought to have evolved over thirty million years ago, was the largest marsupial predator to have survived into historic times. Its historic habitat included the entire mainland of Australia and New Guinea, as well as Tasmania. With the introduction of dingos and dogs, both alien species, to Australia and New Guinea, Thylacines had competitors for prey. This competition caused the Thylacine to die out in these locations leaving them one last island on which to survive. Until the arrival of European settlers with their sheep.

Mistakenly called Tasmanian Wolf ( because it was wolf-like in shape) and Tasmanian Tiger ( because of its stripes) this hapless creature did not have a chance of survival against humans. Thylacines, nocturnal hunters, were at the top of the food chain on the island, preying on kangaroos, wallabies, small mammals, and birds. Unfortunately humans got it into their thick heads that Thylacines were sheep eating machines. Thylacine's habitat on Tasmania was in open gum forest and grassy meadows, never in the dense rain forest of the western mountains. Their lairs were in rocky outcroppings. As an adult, the Thylacine, would weigh approximately 65 pounds (German Shepherd dog size). A female carried her litter of two or three joeys in a backward facing pouch.

Van Dieman's Land Company was the largest of the wool growing operations to move to the island of Tasmania. Gum forests were logged, converting the land into pastures. Sheep were brought to Tasmania in 1824. They were settled into these newly converted pastures as well as the native grassy lowlands and savannah areas, forcing the Thylacines out of their native habitat.

Because of the ill-conceived notion that Thylacines were vicious livestock killers, the Van Dieman Land Company put a bounty out on Thylacine carcasses. The government also paid a bounty on each scalp that was brought in. From 1830 to 1909 thousands of Thylacines were killed. Their hides shipped to London to be made into waistcoats. In 1909 the government quit paying bounties.

By 1909 it was rare to see a Thylacine and the prices paid by zoos for live specimens rose. Trappers now tried to keep the Thylacines alive if they caught one. It is believed that this last Thylacine was captured along with two siblings and mother by a trapper, Walter Mullins, and sold to the Hobart Zoo in 1924. The mother did not survive very long in captivity and the siblings died during the early 1930s.

The story of the incarcerated animals in Hobart Zoo beginning in 1930 is a sad tale. If you want to know the whole story, I suggest you read Robert Paddle's account in his book, The Last Tasmanian Tiger, pg 174-195. The last Thylacine, a female, died because of human neglect. Temperatures in her concrete floored cage during the month of September varied from 90 degrees Fahrenheit in the day to below freezing at night for almost two weeks. One lone deciduous tree outside her cage had lost its leaves offering no shade during the day. The door into her den was bolted offering no escape from the bitterly cold nights.

The last Thylacine died during the night of 7 September 1936 unprotected and exposed to the elements.

On a final note, the zoos Bengal Tiger died on 24 July 1936, also a victim of neglect. The pair of lions survived another year until the zoo was closed on 25 November 1937. No buyer could be found for the lions so they were shot.

No comments:

Post a Comment